Here’s what every federal agency needs to learn from the phenomenal success of Operation Warp Speed.

Blog

The Human Movement

Maybe it’s time for a bold collaborative effort in management. By working together, could we light the fires of management innovation in thousands of organizations?

Busting Bureaucracy

Our institutions change when we change. It’s time to admit what we have long known: our organizations are at odds with our values.

Share Your Story of Bureaucratic Lunacy

We bet you hate bureaucracy as much as we do. Every day it squanders vast quantities of human initiative and imagination. It makes our organizations inertial and incremental. If we’re going to change this, we need first-person accounts of bureaucratic lunacy.

What We Learned About Bureaucracy from 7,000 HBR Readers

We asked members of the HBR community to gauge the extent of “bureaucratic sclerosis” within their organization using our Bureaucracy Mass Index (BMI) tool. Here are our initial takeaways:

Calculating your BMI (Bureaucracy Mass Index)

Do you know how much bureaucracy is really costing your organization? It’s probably more than you think. Here’s how you can estimate your organization’s BMI.

Why Silicon Valley Doesn’t Matter (Much)

In recent years American productivity growth has been anemic, averaging just 0.5% per year from 2010 to 2016. When productivity growth stagnates, so do incomes and living standards. As any economist will tell you, productivity depends critically on innovation—in operations, products, services, and management practices. Historically, innovation has accounted for about half of US productivity growth, the rest coming from enhanced workforce skills and higher capital spending.

Excess Management Is Costing the U.S. $3 Trillion Per Year

More people are working in big, bureaucratic organizations than ever before. Yet there’s compelling evidence that bureaucracy creates a significant drag on productivity and organizational resilience and innovation. By our reckoning, the cost of excess bureaucracy in the U.S. economy amounts to more than $3 trillion in lost economic output, or about 17% of GDP.

More of Us Are Working in Big Bureaucratic Organizations than Ever Before

Writing for the Harvard Business Review in 1988, Peter Drucker predicted that in 20 years the average organization would have slashed the number of management layers by half and shrunk its managerial ranks by two-thirds. Unfortunately, it hasn’t turned out that way. Despite all of the hype around alternatives — the gig economy, the sharing economy, holacracy, lean – bureaucracy has been growing, not shrinking.

The $3 Trillion Prize for Busting Bureaucracy

Around the world, productivity growth has stalled out. While some hope that a “second machine age” will reverse the slump, we think that wringing bureaucracy out of the economy offers a more promising and less speculative route to boosting productivity. By our calculations, busting bureaucracy would add $3 trillion to economic growth in the US alone. Dismantling bureaucracy won’t be easy, but it has to happen—bureaucracy must die. The $3 Trillion Prize provides a detailed blueprint for abolishing the bureaucracy tax in your organization, and everywhere else.

Top-Down Solutions Like Holacracy Won’t Fix Bureaucracy

Busting bureaucracy requires finesse, not brute force. This is a lesson Zappos is learning the hard way. If you want to reduce the bureaucratic drag in your company, you’ll need an approach to change that is emergent, collaborative, iterative and prudent. The key: revolutionary goals and evolutionary means.

The 5 Requirements of a Truly Innovative Company

Can you think of any business topic that’s been hotter for longer than innovation? Trouble is, it’s hard to think of any business challenge where real progress has been harder to come by. By now, your company probably has a new business incubator, an idea wiki, a disciplined process for mining customer insights, an awards program for successful innovators, and maybe even an outpost in Silicon Valley—all fine ideas—and yet, most likely, it still struggles to meet its growth goals and seldom thrills its customers.

The Heart of Innovation

Innovation starts with the heart—with a passion for improving the lives of those around you. When the iPad was introduced, Jony Ive, Apple’s head of design, talked about his passion for creating things that seemed “magical”—that were so far beyond what any customer might have imagined, they seemed like wizardry. You don’t achieve this by paying attention to customers, by putting them first, or even delighting them. You do it by setting out to amaze them—and it all begins with an attitude.

The 15 Diseases of Leadership, According to Pope Francis

Pope Francis has made no secret of his intention to radically reform the administrative structures of the Catholic church, which he regards as insular, imperious, and bureaucratic. He understands that in a hyper-kinetic world, inward-looking and self-obsessed leaders are a liability. Last year, just before Christmas, the Pope addressed the leaders of the Roman Curia — the Cardinals and other officials who are charged with running the...

Reinventing Management at the Mashup: Architecture & Ideology

Large organizations of all types suffer from an assortment of congenital disabilities that no amount of incremental therapy can cure. First, they are inertial. They are frequently caught out by the future and seldom change in the absence of a crisis. Deep change, when it happens, is belated and convulsive, and typically requires an overhaul of the leadership team.

Bureaucracy Must Die

Almost 25 years ago in the pages of HBR, C.K. Prahalad and I urged managers to think in a different way about the building blocks of competitive success. We argued that a business should be seen as a portfolio of “core competencies” as well as a portfolio of products. By building and nurturing deep, hard-to-replicate skills, an organization could fatten margins and fuel growth. While I still believe that distinctive capabilities are essential to distinctive performance, I have increasingly come to believethat even the most...

The Core Incompetencies of the Corporation

Large organizations of all types suffer from an assortment of congenital disabilities that no amount of incremental therapy can cure. First, they are inertial. They are frequently caught out by the future and seldom change in the absence of a crisis. Deep change, when it happens, is belated and convulsive, and typically requires an overhaul of the leadership team.

Build a change platform, not a change program

Transformational-change initiatives have a dismal track record. In 1996, Harvard Business School professor John Kotter claimed that nearly 70 percent of large-scale change programs didn’t meet their goals,1 and virtually every survey since has shown similar results. Why is change so confounding? We don’t think the issue lies with an understanding of its building blocks—Kotter’s classic eight-step change-management model is still a helpful guide.

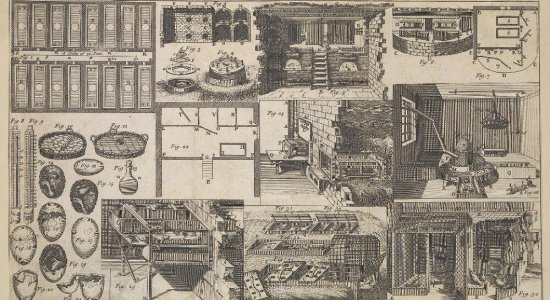

The next tech revolution: Busting bureaucracy

Over the past 20 years, nothing has transformed business as thoroughly or as frequently as information technology. In the first wave, advances in IT prompted many companies to revamp their operating models. In Wave 2, the growing power of the Web provoked a fundamental rethink of business models. And over the next few years, Wave 3 will yield a broad-based and long overdue revolution in management models.

The Leaders Everywhere Challenge

Never before has leadership been so critical, and never before has it seemed in such short supply. It takes extraordinary leadership to keep an organization relevant in a world of relentless change. It takes extraordinary leadership to navigate the complexities of global supply chains, industry ecosystems, and labyrinthine regulation. And it takes extraordinary leadership to unleash the human capabilities—initiative, imagination and passion—that fuel success in the “creative economy.”